Deadly crash sparks firefighter safety concerns: Lithium car batteries pose multiple problems

Volunteer fire departments are facing a new kind of challenge: burgeoning electric vehicle technologies.

First responders faced this challenge the night of Feb. 24 in East Marion when two vehicles, a 2020 Ford Explorer and a 2023 electric Tesla equipped with a lithium-ion battery, collided head-on.

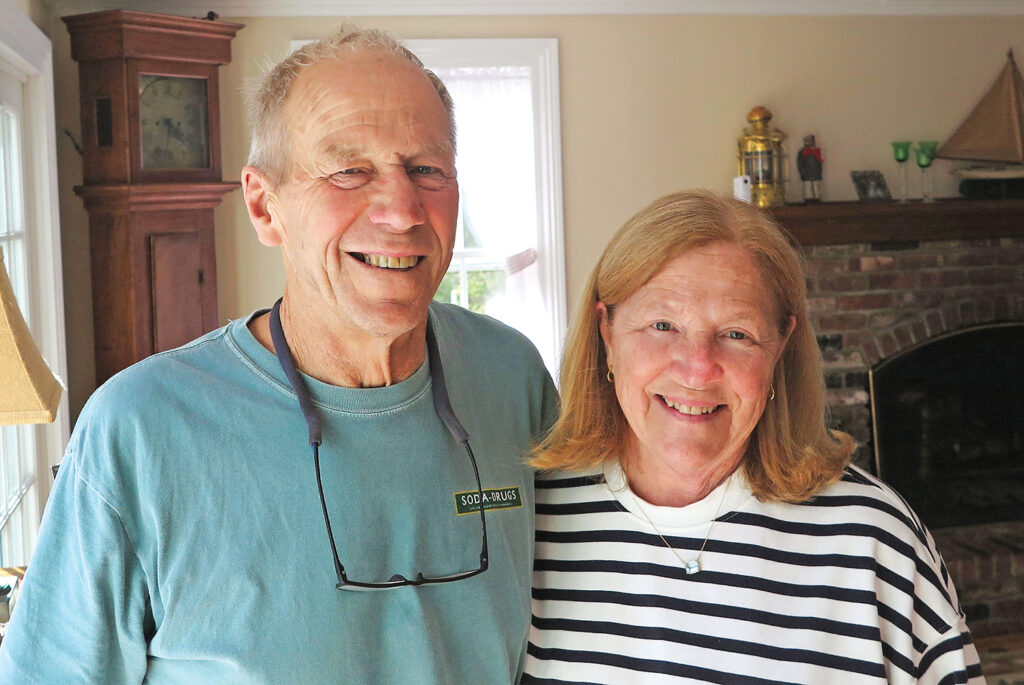

Two passengers in each car died. Police identified them as Heath Miller, 47, of Greenport; William Price, 55, of Wilton, Conn.; Peter Smith, 80 and Patricia O’Neill, 66, both of Brooklyn and Orient. Because of the Tesla’s lithium battery, first responders had a difficult time putting out the fire, which burned for two hours and produced heavy smoke.

“Fire departments had a very difficult time putting it out because it was a lithium battery on an electric vehicle,” Southold Police Chief Martin Flatley said. “Usually with gas engines, they are a lot easier to put out either with water or chemicals. But this fire burned pretty hard and pretty intense.”

East Marion, Orient and Southold fire departments, Southold Town police and the Suffolk County Police Emergency Services Unit all responded to the accident. The Southold Town Police Department and the New York State Police accident reconstruction team are conducting an investigation into the accident.

As more cars and trucks begin to use lithium-ion batteries, the potential hazards of the technology have become apparent. With regards to electric vehicles, fires involving Teslas made recent headlines when a spontaneous battery combustion in California caused a car fire which required 6,000 gallons of water to extinguish.

On the North Fork, two Battery Energy Storage System facilities, essential for the growth of renewable energy, have been proposed and highly contested.

In January, the Riverhead Town Board voted to retain BFJ Planning of Manhattan as a consultant for a BESS facility even as the town code is being amended to include BESS facilities.

Last month, Southold Town Supervisor Scott Russell proposed a 12-month moratorium on BESS facilities, and the board has set a public hearing on the moratorium for March 14.

Fires involving lithium-ion batteries produce intense heat, far more than a standard car fire, and local departments must adapt to this new challenge. Since 2021, the Suffolk County Fire Academy in Yaphank has offered training lectures specifically regarding lithium-ion batteries at firehouses throughout the county.

Chief Rudolph Sunderman, deputy director of the Suffolk County Fire Academy, said the academy wants to educate firefighters “to be prepared for the hazards that are associated with the technologies.”

These hazards are not limited to fire departments, but all first responders. Chief Flatley said several of his officers who responded to the scene that evening experienced shortness of breath following the ordeal, but that none required hospitalization.

“The Tesla was on fire in the middle of the roadway, and the wind was blowing extremely hard off the Sound out of the north,” he explained. The car “gave off a really heavy gray smoke that was billowing around the accident scene and the wind was blowing it towards the other vehicle that was involved in the accident, so it made it very difficult for the officers who responded to be able to get near either one of the vehicles because of the intense smoke that was involved.”

When firefighters respond to battery fires, Suffolk County Fire Academy literature instructs them to “apply water directly to the battery. If safety permits, lift or tilt the vehicle for more direct access to the battery.”

Shelter Island Fire District Commissioner Keith Clark, who has been a firefighter for many years, addressed the issue with the Reporter, noting he was not speaking in his role as a commissioner. Mr. Clark said electric vehicles pose dangers of fires that are not only difficult to extinguish, but electrocution is another possibility with the vehicles.

“There’s not only a danger to those who are drivers and passengers in an electric vehicle, but to first responders trying to extinguish a fire,” he added.

As an aside, Mr. Clark noted that solar panels on buildings also add an element to how firefighters address blazes that have the panels. Although they can be shut down, he said they still hold power for 24 hours and can be difficult to extinguish.

Safely accessing the undercarriage of a burning electric vehicle is not an easy task, and some local fire departments have been exploring methods of reaching the battery.

Greenport Fire Department Secretary James Kalin told The Suffolk Times his department held a training course earlier this month regarding electric vehicle fires. The training included the use of a cellar nozzle, a piece of equipment he described as “a giant lawn sprinkler,” to apply water to undercarriage batteries more directly.

“It’s old technology, and now they’re adapting it for electric vehicles where it slides underneath the car and spins around to put water up on the battery case,” Mr. Kalin said. “When a car’s that low, how do you apply water to the battery case when you can’t get under it?”

Experts said lithium-ion battery fires are still too new for a consensus to be reached regarding best methods for putting them out. “The battery is the whole bottom of the car, and once it goes on fire, the tires flatten out and it drops down even more, so it’s on the ground and you can’t get the water underneath it,” said Carleton Raab, the president of the North Fork Volunteer Firemen’s Association and a member of the East Marion Fire Department for more than four decades. “Our solution was, we dumped 11,000 gallons of water on it. What generates innovation is experience. You’re going to have enough different situations to find out what’s the best way. Right now, all we know is just pour the water on it.”